Towards a new era for health and wellbeing?

It would be fair to say that a lot of people (myself included) didn’t see COVID-19 coming. Some countries had pandemic plans in place, and some, like Australia, New Zealand, Denmark and Vietnam, mobilised quickly to suppress the disease. The leadership of countries that engaged with public health and scientific advice early are clearly better positioned to emerge from the crisis sooner, and to rebuild their economies and social fabric.

As COVID-19 unfolded I was reminded of someone who in a way did see this coming. Pim Martens of Maastricht University in the Netherlands wrote an insightful article back in 2002, where he explored the idea of health transitions, and asked if we are tracking towards more disease or sustained health. His reflections offer important considerations now as we look to what a post-COVID world could look like for the health of populations across the world.

Taking a public health perspective

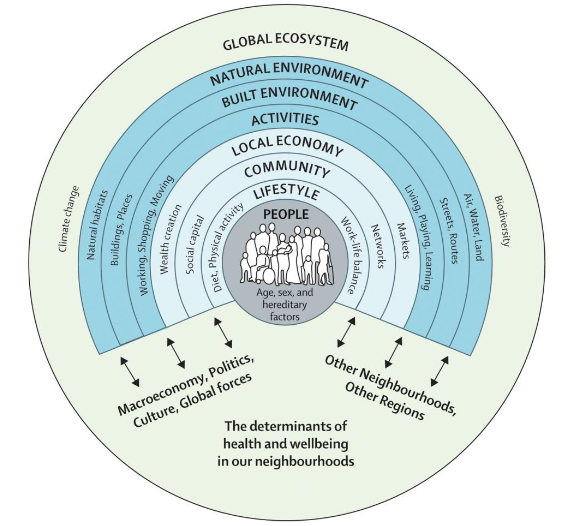

Martens explored how the health of populations has moved through different transitions over time, and approached this from a public health perspective, which recognises a wide range of factors influence our health and wellbeing, far beyond just health services and health technology.

Source: Barton and Grant 2006

As Louise Thornley wrote in this excellent piece, public health is about “stopping illness before it strikes, and helping create healthier policies and places where all people can live fuller, healthier lives.” It’s about how health is affected by our education, our access to food and water, our incomes, our ecosystems and biodiversity, and our access to health services. These all interconnect to influence the health of individuals and communities.

In New Zealand and elsewhere, good health is not evenly distributed across all populations, but rather there are ‘social gradients’ where those with higher incomes and education opportunities tend to have better health. In New Zealand, it means for example that Māori, Pacific and migrant communities often suffer the poorest health. This is only partly explained by health behaviours; the everyday settings in which health decisions are made, where people work and learn, and where lives are simply lived, also determine the health of populations.

The circular diagram here is a classic representation of the many factors that impact on people’s health.

Health transitions

Martens put forward the idea of the ‘health transition’, which proposes that social, economic and ecological changes have driven changes in the health of populations. Martens proposes three transitions, or ‘ages’ that have characterised our development to date:

The age of pestilence and famine: This has prevailed through most of human history, where epidemics, famines and wars cause large numbers of deaths, and basic resources such as food and fresh water are often inadequate. Lack of basic infrastructure such as schooling and sewage systems lead to low levels of literacy and high levels of mortality and fertility. Some developing countries remain in this stage.

The age of receding pandemics: Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century in places we now call developed countries, this age is marked by a reduction in infectious diseases, diseases related to malnutrition and a fall in mortality rates. Improved use of natural resources and development of infrastructure such as clean water and waste systems, together propel economic growth and health improvement, and improved social circumstances further improve both health and economic development. The introduction of modern healthcare and health technologies enable the control and elimination of many infectious diseases. Yet this age also carries the seeds of future health and economic decline, as the carrying capacity of local ecosystems and resources are exceeded.

The age of chronic diseases: As infectious disease recedes, chronic diseases such as heart disease and type 2 diabetes increase. Health patterns become increasingly influenced by behaviours such as food consumption, physical activity, and use of alcohol and other drugs; (I would strongly argue these are in turn influenced by a range of factors, including poverty and inequity, government regulation, infrastructure that supports healthy living, and industry behaviour).

Martens argued that most developed nations have reached the third age of the health transition. In developing nations, the health transition varies greatly, and some experience a double burden of infectious disease and chronic disease.

Next stages in health transitions

Martens suggested three potential further ages in health, which today seem prescient:

The age of emerging infectious diseases: The emergence of new diseases, or the re-emergence of old diseases will significantly impact health. These are influenced by patterns of travel and trade, microbiological resistance, human behaviour, shortfalls or breakdowns of health systems, and environmental pressures. Ill health will lead to lower levels of economic activity, and poorer countries, will be caught in a downward spiral of environmental decay, depressed incomes and poor health.

The age of medical technology: Economic growth and technological improvements can offset the health risks caused by changes in lifestyle and environmental changes. But this stage is not endpoint in itself, and without sustainable economic development, societies may be propelled into the age of infectious diseases.

The age of sustained health: Investments in public health, education and welfare services support a reduction in lifestyle-related diseases and most environmentally-related infectious diseases are eradicated. Health policies are designed to ensure the health of future generations are not compromised by the depletion of resources that they will need. Health systems are well adjusted to supporting older populations, and worldwide disease surveillance and monitoring systems enable any infectious disease outbreaks to be dealt with effectively.

The diagram below is an adaptation of how Martens presented the concept of health transitions.

Reflections in the light of COVID-19

It is easy to see the spread of COVID-19 as a signal of an age of emerging infectious disease. COVID-19 has spread rapidly across the globe, and is accelerated to some extent by those who are asymptomatic (or pre-symptomatic) and yet harbour the disease before passing it on to others. Older people and those with underlying health conditions are particularly at risk.

Yet one could also say that COVID-19 has emerged in an age of medical technology, where in many countries, health investment has been increasingly concentrated in new treatments, often at the expense of investment in public health. We have seen with COVID-19 that a reliance on medical technology by its nature won’t prevent the spread of infectious disease, and this reliance has left health services exposed to a rapid growth of cases beyond their capacity to meet them; countries like Italy, Spain and the United States have had to repurpose facilities to deal with the influx of cases, and sadly to also store the bodies of those who have lost their lives. COVID-19 has forced a rapid escalation of public health services investment to meet the challenge, particularly of widespread testing and contact tracing.

In dealing with COVID-19, countries such as New Zealand, Australia, Taiwan and Vietnam have pursued, in the short-term, policies of social isolation to limit spread, accompanied by extensive testing, contact tracing, and treatment. Public investment in wage support is partially cushioning the financial impact for many businesses. The success of these approaches has relied on the concerted working across sectors – health agencies in the immediate response, police in enforcement, education and social service providers in adapting their delivery to enable continued engagement, and the private sector in acknowledging the scale of the problem and responding accordingly – all in the hope of off-setting even larger economic and social losses through uncontrolled spread of the disease.

Towards sustained health?

To my mind, it is where the successes to date in battling COVID-19 give us a signal of how we might take steps towards an age of sustained health. Not simply in terms of the interventions themselves, but in how every sector of society has swung in behind the goal of eliminating COVID-19. In New Zealand, the collective working of government, science, medicine, social sectors and industry have created the foundations for what we hope will be a lasting success and a platform for rebuilding the economy.

The fiscal cost of responding to COVID-19 will leave a huge debt to future generations, on top of the debt they already potentially face through the costs of climate change (and yes, that issue still remains). I believe that we owe our future generations a response to COVID-19 that offers more than a vaccine or another treatment – as welcome as these will be.

We need a long-term response to COVID-19 that will ensure we are not marooned where we are now – in a hybrid world of infectious disease and advanced medical technology. We need a policy mix that will take us towards sustained health.

So I would argue if we are to work towards an age of sustained health, we need to orient our economic stimulus towards those areas of the economy that will improve the health and wellbeing of people and ecosystems today, and for generations in the future. I am struck by both the alignment and diversity of ideas from New Zealand commentators such as Rod Oram, Janet Stephenson and indigenous leaders, as well as from organisations like the Lever Room, Koi Tū, the Sustainable Business Network and the Sustainable Business Council. These and others offer compelling directions for the world beyond COVID. They include:

Restoring and strengthening the conservation estate, biodiversity and waterways for future generations

Investing in sustainable buildings, industries and cities

Ensuring access to safe, affordable and comfortable housing

Fostering sustainable procurement, that supports better outcomes for people and the environment

Targeting recovery towards vulnerable communities

Building infrastructure that encompasses digital, natural, cultural and social elements

Investing in low-carbon active mobility systems

Increasing investment in publicly funded, public good, public health research

Integrating indigenous voices and perspectives throughout the recovery process

Supporting regenerative industries that work in tandem with nature

Investing in waste minimisation and circular economies that emphasise repair and reuse

Together, they offer a path to a healthier, sustainable and resilient future. These complement and build on the gains from medical advances, but don’t rely on medicine alone to deliver on population health.

Across all this we need a strengthened public health infrastructure to monitor the health and wellbeing of people and communities, respond to and advocate on critical health issues, and to be part of the dialogue on a building the new economy.

The very different paths, and the very different levels of success, enjoyed by different countries in their responses to COVID-19 shows us that widespread illness and mortality is not inevitable. Similarly, a path to achieving sustained health is a choice we can make.

The scale of disruption of COVID-19 means that a return to business as usual was never on the cards, and even before COVID-19 business as usual wasn’t a viable solution. But the recovery provides an opportunity to chart a better course for our future. And in the same way that dealing with COVID-19 in the short-term requires a collective effort, building a healthier and more sustainable future in the long-term will require the collective efforts of all sectors and communities.

The full reference for Pim Martens article is: Martens P. 2002. Health transitions in a globalising world: towards more disease or sustained health? Futures. 34 (7): 635-648. The public health diagram is sourced from Barton H, Grant M. 2006. A health map for the local human habitat. The Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health. 126(6):252–3